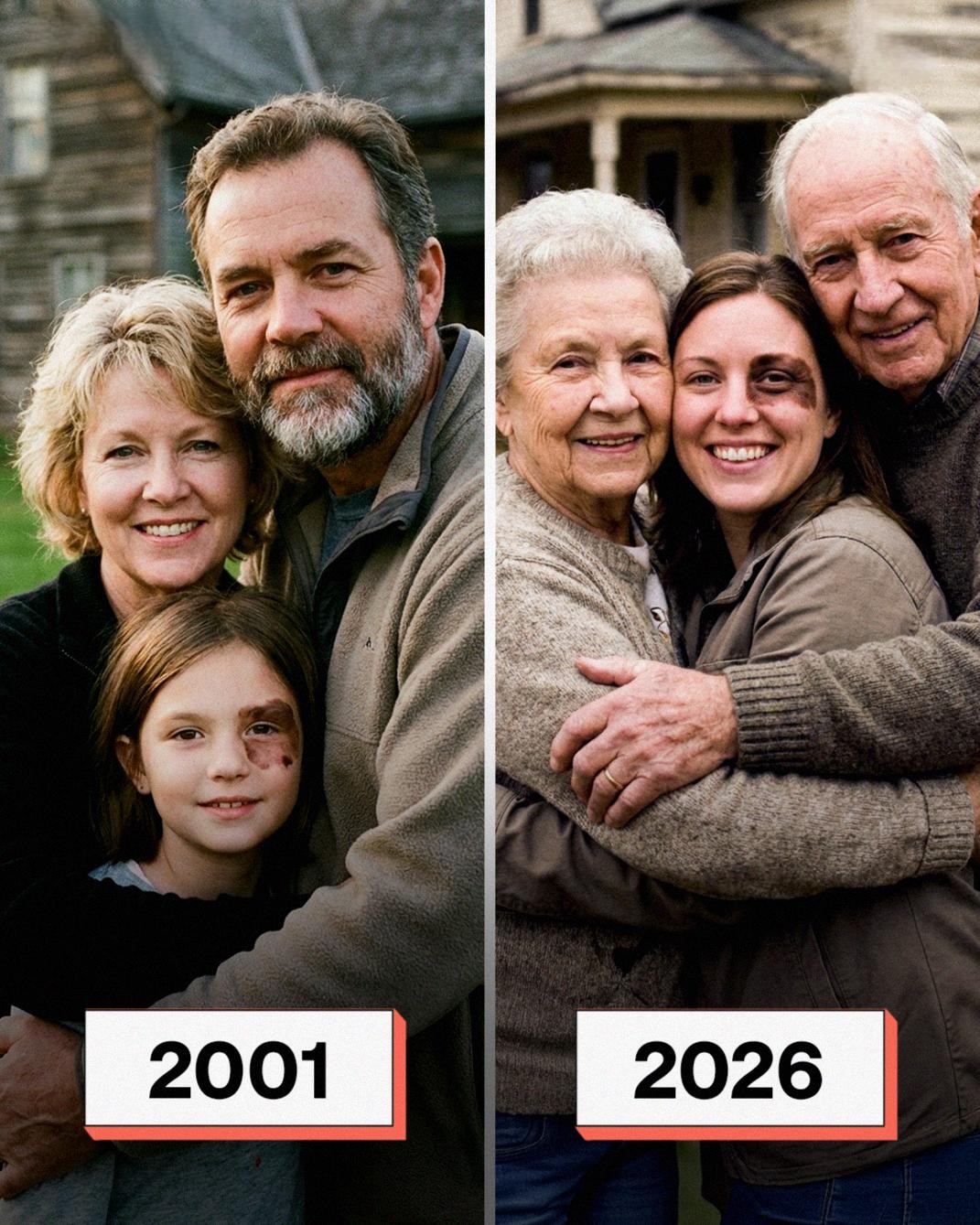

I am seventy-five years old now, an age that still surprises me when I say it aloud. My name is Margaret, and for more than half a century, my life has been intertwined with one man—my husband, Thomas. We have been married for over fifty years, sharing decades that were sometimes loud with laughter and sometimes painfully quiet, but always grounded in companionship.

For most of our marriage, it was just the two of us. No children’s voices echoed through our hallways. No small shoes by the door. No drawings taped to the refrigerator. That absence wasn’t something we planned—it was something that happened to us, slowly and then all at once.

We wanted children deeply. That desire lived with us from the earliest years of our marriage. We tried in ways that were hopeful at first and then increasingly clinical. There were doctor’s offices with pale walls and ticking clocks, endless tests whose names blurred together, hormone treatments that made my body feel unfamiliar, and calendars carefully marked with circles and stars. Each month carried its own fragile hope, followed almost inevitably by disappointment. We endured this cycle far longer than most people ever knew, because infertility is a grief people rarely talk about openly.

Eventually, there came a day when the pretending ended. A doctor sat across from us, hands folded, voice careful. He spoke gently, but his words landed heavily. He said our chances were extremely low—so low that continuing would likely bring nothing but further heartbreak. There were no alternative plans offered, no reassurance that science might someday catch up to our hopes. That conversation marked the end of something we had been fighting for, quietly but fiercely.

We mourned in our own way. There were no dramatic scenes, no outward collapse. Instead, we learned how to carry the loss with us. Life continued. We grew older. By the time I reached fifty, Thomas and I told ourselves that we had accepted the life we had. We had built routines meant for two people. We traveled, filled our days with work and hobbies, and convinced ourselves that contentment was enough.

Then one ordinary afternoon, everything shifted.

Mrs. Collins, who lived three houses down, stopped me while I was tending the front garden. She was the sort of woman who always seemed busy, always involved in something charitable. She mentioned casually that she volunteered at the local children’s home. Her voice was light, as though she were commenting on a change in the weather.

“There’s a little girl there,” she said. “She’s been waiting for a family for five years now. No one ever comes back for her.”

I asked why, without fully understanding why my heart had already begun to race.

Mrs. Collins hesitated only briefly. “She was born with a large birthmark on her face,” she explained. “People ask for pictures. Then they decide it’s too much. She’s been there since she was born.”

That night, sleep wouldn’t come. I lay awake imagining a child learning, again and again, that she was not chosen. A child watching visitors come and go, understanding more than adults realized. I thought of how rejection might carve itself into someone so young, shaping the way she saw herself before she ever had a chance to decide who she was.

When I finally told Thomas, I expected resistance. We were older, after all. Our lives were orderly and predictable. We had settled into the rhythms of age, not the chaos of raising a child.

But Thomas didn’t dismiss me. He listened carefully, then looked at me and said simply, “You can’t stop thinking about her, can you?”

He was right.

We talked honestly in the days that followed. We discussed our age, our stamina, and our finances. We talked about what might happen if we didn’t live long enough to see her grow into adulthood. There were no grand declarations or sentimental speeches—just facts laid bare. It was the most serious conversation we had had in years.

In the end, Thomas said, “Let’s meet her. No promises. Just meet her.”

Two days later, we walked into the children’s home.

A social worker greeted us and led us down a hallway filled with soft voices and the distant sound of toys. She explained carefully that the child—her name was Lily—knew only that visitors were coming. They didn’t want to give her false hope.

Lily sat at a small table, coloring with intense focus. Her dress was slightly too large, clearly handed down. The birthmark covered much of the left side of her face, dark and impossible to ignore. But her eyes were alert, watchful. They were the eyes of a child who had learned to study adults closely.

I knelt beside her and introduced myself. Thomas did the same.

She looked at him thoughtfully and asked, “Are you old?”

Thomas smiled. “Older than you.”

She paused, considering this. Then she asked, with unsettling seriousness, “Will you die soon?”

My breath caught. But Thomas answered without hesitation. “Not if I can help it. I plan to be annoying for a very long time.”

That earned a brief smile—quick and guarded—before she returned to her coloring.

She was polite, but distant. She kept glancing toward the door, clearly measuring how long we might stay.

The adoption process took months. Paperwork, interviews, home visits—it all moved at a pace that felt painfully slow. When it was finally complete, Lily left the children’s home carrying a small backpack and a worn stuffed rabbit, held tightly by one ear.

In the car, she asked quietly, “Is this really my house now?”

“Yes,” I said.

“For how long?”

Thomas turned in his seat. “Forever. We’re your parents.”

She didn’t cry. She simply nodded, storing the words away, waiting to see if they would prove true.

The early weeks were difficult. Lily asked permission for everything—where to sit, when to eat, whether she could speak. It was as if she were trying to take up as little space as possible, afraid of being sent back.

One night, she whispered, “If I do something bad, will you send me away?”

“No,” I told her gently. “You might get in trouble. But you won’t be sent away. You belong here.”

She heard me, but it took time before she believed it.

School brought new challenges. Children can be cruel without understanding the damage they cause. One day, Lily came home silent, eyes swollen. A boy had called her a monster. Others had laughed.

I pulled the car over and looked her in the eyes. “You are not a monster,” I said. “Anyone who says that is wrong.”

She touched her cheek and said she wished the mark would disappear.

“I don’t,” I replied. “I wish the world were kinder.”

We never hid the truth about her adoption. When she was thirteen, she asked about her biological mother. All we could tell her was that the woman had been very young and left no letter.

“I don’t think you forget a baby you carried,” I said.

Lily nodded, but I felt something tighten in her.

As she grew older, she learned to speak confidently. By sixteen, she told us she wanted to be a doctor—someone who could help children feel whole.

She kept that promise. College. Medical school. Exhausting nights. She never gave up.

By the time she graduated, Thomas and I had slowed down. Lily called daily, visited weekly, and scolded me about my diet like one of her patients.

Then the letter arrived.

Inside were three pages written by a woman named Emily—Lily’s biological mother. She explained everything. The fear. The pressure. The regret. She was ill now, she wrote, and wanted Lily to know she had been loved.

We gave Lily the letter.

She cried quietly, then said, “You’re my parents. That doesn’t change.”

She chose to meet Emily.

The meeting was painful, gentle, and incomplete. There were apologies that couldn’t erase time, and sadness that lingered.

Later, Lily said the truth hadn’t fixed everything.

“It ended the wondering,” I told her.

Today, Lily knows she was wanted twice—by a frightened girl who had no power, and by two people who knew she was never unwanted at all.